Why a 55 per cent tax charge is far from the death knell for pension planning despite the claims of some concerned retirement advice experts, by Neil MacGillivray from James Hay Partnership.

One of the best pieces of advice I can give when it comes to tax planning is always to consider the impact of all taxes over the life of a client. Too often in an attempt to save tax in the short term, a larger potential liability is left lurking in the background.

Nothing demonstrates this better than the reaction by some people to the introduction of the 55 per cent recovery charge on pension schemes introduced in this year’s Finance Act as part of the changes which also allowed member’s funds to remain uncrystallised on or after their 75th birthday. The removal of the need to crystallise benefits before age 75 provides a greater degree of flexibility for retirement planning, increasing the choices available as to when and how pension benefits are taken. This is particularly beneficial at a time when annuity rates seem set to continue to remain low for the foreseeable future.

The perceived downside is the 55 per cent recovery charge now to be applied on authorised death benefit lump sum payments paid out of all crystallised and uncrystallised funds for members aged 75 or over. The knee jerk reaction by many members is that the recovery charge is excessive, and is to be avoided if at all possible. This has led to those who are taking benefits to look at how they can strip out as much income from their pension fund where it will be taxed at a lower rate and alternatively, for those still contributing to their pension, to question if there is value in continuing to do so.

However, is a tax charge of 55 per cent really that excessive?

UK pensions are treated on an exempt-exempt-taxed basis: in other words, no tax on the money entering the pension, no tax on the pension funds (except of course for the non reclaimable 10 per cent dividend tax credit) with tax eventually being paid when benefits are paid out to the member. Given this beneficial tax treatment, how do pensions compare to other tax wrappers, such as Isas and offshore bonds?

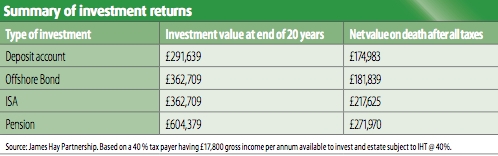

If we consider the full tax implications of a fixed amount invested annually over a 20 year period in to a bank account, Isa, offshore bond and a personal pension, the final value of the funds after all taxation could yield surprising results. The following examples are somewhat basic, and do not consider charges; their aim is to demonstrate the impact of all taxation on investments over the life of an investor.

A higher rate taxpayer investing £10,680 a year into a bank account paying 5 per cent gross (3 per cent net) interest per annum would at the end of 20 years have accrued a total fund of £291,639. If the same amount was invested in an Isa or an offshore bond and a gross return of 5 per cent per annum achieved, the fund would be worth £362,709. The Isa has of course the advantage of being able to access the full fund without any charge to income or capital gains tax. Under the offshore bond the investor could extract the original sum invested over time, with no immediate tax charge, and although deferring income tax, the growth would eventually be taxed as income. Again to keep matters simple, presuming the growth was taxed at 40 per cent, on full encashment the net value of the fund would be £303,065.

A pension has the advantage over the Isa and the offshore bond in that any contributions made, providing they do not give rise to an annual allowance charge and the member has sufficient relevant UK earnings, are paid gross of income tax. The gross annual contribution in this example would be £17,800 per annum; the net of basic rate tax contribution being £14,240 with higher rate tax of £3,560 reclaimed through the investor’s tax return, taking the net cost of the annual contribution to £10,680. The fund would also benefit from tax- free growth, as would the Isa and offshore bond. Not surprisingly, with the benefit of the gross contributions, and a presumed 5 per cent pa gross return, at the end of 20 years the pension fund would be worth considerably more than the other options, with a value of £604,379.

The limitation of course is that normally only 25 per cent of the fund (£151,095) can be taken as a tax free lump sum, when the member is aged at least 55, unless they have major health problems, when benefits may be taken earlier. The remaining fund of £453,284 would be subject to income tax as and when income was taken, and on the death of the investor the unused fund at that time, if paid out as an authorised lump sum death benefit, would be subject to the 55 per cent recovery charge. It may therefore seem, at first glance, that stripping income out under flexible drawdown, even if the member is a higher rate taxpayer, appears an attractive option. However, how do the bank account, Isa and offshore bond funds compare net of taxes after the investor’s death?

Assuming the client in our examples has other assets in excess of the inheritance tax (IHT) nil rate band, then the bank account, Isa and offshore bond funds would be liable to IHT at 40 per cent. The value of the bank account would be reduced to £174,983, the ISA £217,625, and the offshore bond fund after higher rate income tax and IHT £181,839. What about the pension? If the pension commencement lump sum (PCLS) had been taken (and not spent) it would be subject to IHT, leaving a net fund of £90,657. If the crystallised pension fund is paid out as an authorised death benefit lump sum, it would be subject to the 55 per cent recovery charge, leaving the combined net value of the pension fund as £294,635 (assuming the crystallised fund was still worth £453,284), significantly higher than the other options. If benefits had not been taken and the investor died before age 75 then the full fund of £604,379 would be available as a lump sum, or if death occurred on or after age 75, the net value of the fund after the recovery charge would be £271,970.

As the outcome of this simple example amply demonstrates, there may be real value for high net worth individuals to leave their pension funds untouched for as long as possible, while running down other savings to provide income. Stripping income out which is surplus to requirements could lead to an overall higher tax charge. In reality though, there are very few people who can afford not to take an income from their pension, and so for the majority who do require a pension income, they should consider in terms of tax planning, the flexibility afforded by phasing their benefits. Equally, managing pension income prudently could allow the individual to maintain a lower rate of income tax and, if available, flexible drawdown may help facilitate this.

In the case of flexible drawdown, it is important to look at the cost/ benefit of securing enough pension income to meet the minimum income requirement (MIR) of £20,000 per annum. As an example, for a male aged 65 using an annuity to supplement his state pension with a further £15,000 pa to meet the MIR requirement; on a level, single life basis, with no guarantee, he would have to pay a sum in the region of £250,000* to secure this income. In comparison, taking the maximum of a 100 per cent of GAD rate for October of 2.75 per cent, a 65 year old would secure a pension of £14,240 with a fund of £250,000 under drawdown. Though slightly less, and not guaranteed as is the case under the annuity, there is the possibility of income increasing in the future, as well as part of the fund being passed on when the member dies.

Tax relief on pension contributions has long been held as one of the ‘carrots’ for justifying pension contributions, and according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies the reduction in the higher rate threshold in 2011/12 has placed an additional 750,000 individuals into the higher rate tax bracket. With further reductions in the higher rate tax threshold planned, a greater proportion of taxpayers will move into the higher rate.

Also to be considered is the temporary additional rate of tax at 50 per cent for those with income in excess of £150,000, and individuals earning between £100,000 and £114,950 paying income tax at an effective rate of 60 per cent due to the loss of their personal allowance. In effect this means more people will benefit from tax relief at a higher rate and they should be encouraged to maximise their contributions if they can afford to do so while it lasts. Rachel Reeves, during her short time as shadow pensions minister, stated that too much Government money was being used on the pension tax relief of high earners, a view shared by the Liberal Democrats.

Therefore, could tax relief in future be restricted to basic rate and would this make pensions unattractive to higher rate tax payers? Based on the figures earlier if the client only received relief at basic rate on his contributions, his fund would still be worth £483,340 at the end of 20 years. Even on the worse case scenario of the whole fund being taxed at 55 per cent, the net return on death after taxes still matches the Isa. The recovery charge of 55 per cent at first glance appears unpalatable, however like any tax, it should not be considered in isolation. Though it may seem a somewhat depressing thought, it could actually be generous!